Low participation rates, late diagnoses and younger patients point to the urgent need for a rethink.

Some recent health statistics paint a troubling picture.

The latest National Population Health Survey from the Ministry of Health shows that just 35.2 per cent of Singapore women aged 50 to 69 go for mammograms to get screened for breast cancer. Cervical and colorectal cancer screening rates are slightly higher at 44.9 per cent each, but still inadequate.

These numbers are made more concerning by data from the Singapore Cancer Registry’s latest annual report. Between 2019 and 2023, there were 4,995 cancer diagnoses for those under 40 – a 34 per cent increase from the 3,729 cases recorded between 2003 and 2007. Breast cancer is most common among younger women. Colorectal cancer rates have increased in young adults over the long term.

While rising cancer incidence among younger adults reflects a global trend, Singapore remains considerably behind global counterparts and international benchmarks when it comes to screening participation. This is despite having well-established national screening programmes in place.

The widening gap between policy design and public uptake, at a time when cancer is increasingly affecting younger people, makes it imperative to understand and address the reasons behind it.

The complexity behind low participation

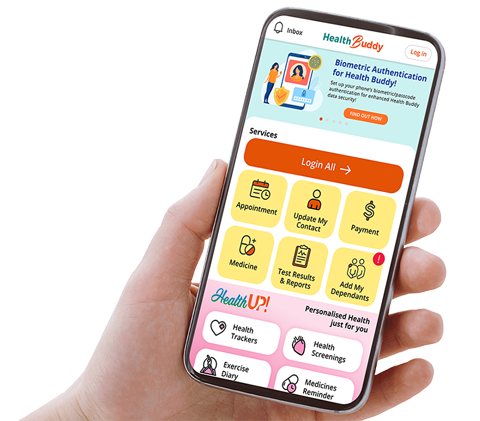

In Singapore, cancer screening is recommended through the Healthier SG programme for early detection, focusing on breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers.

Women aged 50 to 69 are recommended to have mammography screening every two years. For women under 50, screening recommendations should be individualised based on personal risk factors, family history, and clinical assessment in consultation with their healthcare provider.

Cervical cancer screening either by Pap smear every three years or human papillomavirus (HPV) test every five years is recommended for women who are sexually active. Screening for colorectal cancer via an annual faecal immunochemical test (FIT) is recommended for all adults from the age of 50.

Current low participation rates in cancer screening here suggest underlying complex, interconnected barriers that healthcare initiatives have struggled to address effectively.

Psychological barriers remain the most significant challenge. For many, fear of diagnosis is still a powerful deterrent, with some operating under the principle that “ignorance is bliss”.

This fear is compounded by the cultural stigma, where a cancer diagnosis can be perceived as bringing shame or giving a burden to families. In Singapore’s multicultural society, these attitudes vary across ethnic groups but consistently influence screening behaviour.

Misconceptions about cancer screening further complicate participation. Many believe screening is only necessary for individuals who experience symptoms or have a family history of cancer. Others question the accuracy of screening tests or worry about false positives leading to unnecessary procedures, the associated costs and anxiety.

Practical barriers also play a role. While recommended cancer screenings are provided at no cost for eligible Singapore residents under Healthier SG, some worry about the potential financial burden of cancer treatment if there is a positive diagnosis, and this may paradoxically deter them from getting screened. This creates a troubling scenario where the fear of the financial burden of cancer treatment prevents early detection that could in fact reduce both mortality and treatment expenses.

Physical discomfort and the intimate nature of screening procedures such as Pap smears and mammograms, combined with cultural sensitivities, can create psychological barriers, and deter some women from getting screened.

Preventive health is a desired goal but in Singapore’s fast-paced society, where many have competing life priorities juggling work, family and other immediate concerns, prioritising health and screening often takes a back seat.

When cancer comes earlier

With the rise in cancer diagnoses among younger adults, one might wonder if people should start getting screened at an earlier age.

It is important to note that most national screening programmes are made based on scientific evidence and designed for asymptomatic, average-risk individuals.

A screening programme is only recommended if there is strong, good quality evidence over many years that shows that the benefits outweigh the potential harm from overdiagnosis.

While cancer screening is currently not recommended for younger adults, there are some exceptions. Young adults who have a family history of cancer or hereditary cancer syndromes should discuss with their doctors if there is a need to start screenings earlier or more frequently than the general population.

Even so, all individuals, whether young or old, who experience unusual or persistent symptoms, such as unexplained weight loss, persistent fatigue, lumps or swelling, or pain that does not go away, should seek medical advice promptly and not ignore any worrying symptoms.

Early attention to warning signs is important at any age.

Strengthening our strategies

Other countries grappling with similar challenges offer useful lessons.

Australia’s national programmes are organised with centralised invitation systems and comprehensive population registers. Cervical cancer screening participation exceeds 70 per cent thanks to systematic reminders and targeted outreach to underserved communities. Their success stems from treating screening as a population health initiative rather than an individual healthcare decision.

The United Kingdom’s National Health Service employs automatic enrolment systems where eligible individuals receive direct invitations, supported by sophisticated data tracking of non-participants and follow-ups by health visitors.

In the US, colorectal cancer screening has been particularly successful with FIT mail-out programmes, which eliminates the need for clinic visits and reduces barriers to participation. Combining automated mailing systems with electronic health record integration for tracking and follow-up further ensures high screening rates.

Singapore’s screening programmes would benefit from a similarly organised, population-based approach. This includes proactive invitations, integrated data systems to track participation and follow-up, and patient navigation services that help individuals overcome logistical, cultural and emotional barriers.

Tailored outreach and sustained public education campaigns are essential, particularly for underserved communities. They must go beyond building awareness to addressing specific fears, misconceptions, and cultural concerns about screening, by employing trusted spokespeople and culturally appropriate messaging.

The consequences of low screening participation are profound and measurable, extending past statistics to real human suffering and preventable deaths. In Singapore, many cancers are diagnosed at advanced stages, when treatment options are limited, outcomes are poorer, and costs are substantially higher.

A particularly troubling reality is that most cancer deaths arise from cancers that do not currently have validated screening tests. This underscores the importance of maximising participation in existing screening programmes and the urgent need to employ more innovative screening approaches to detect more cancer types early.

Only by embracing new technologies and systematic interventions can we adequately address the complex web of barriers preventing Singaporeans from accessing potentially life-saving cancer screening services.

What’s being done

In this context, the National Cancer Centre Singapore and Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine recently launched the Research Institute for Cancer Prevention, Screening and Early Detection (RISE).

With representation from all three public healthcare clusters in Singapore, working with other partners including the Singapore Translational Cancer Consortium, RISE aims to drive evidence-based policy recommendations and implementation strategies for cancer screening and early detection initiatives in Singapore.

For a start, RISE will assess Multi-Cancer Early Detection (MCED) assays, which have emerged as a potentially transformative approach to address cancer screening challenges. MCEDs work by detecting cancer signals through various biological markers. In addition, advanced platforms can predict the tissue of origin, potentially enabling targeted diagnostic workup.

While not included in national cancer screening guidelines because there is currently insufficient evidence to show that the tests improve population health outcomes, the appeal of MCED technology lies in its potential to address several barriers simultaneously.

A simple blood test could eliminate the physical discomfort associated with traditional screening methods, reduce cultural barriers related to intimate examinations, and potentially detect multiple cancer types simultaneously.

However, careful evaluation is needed to determine whether these tests meaningfully improve outcomes when applied at scale.

A call for comprehensive action

Singapore’s cancer screening challenge requires a coordinated response that reflects changing disease patterns, including the growing impact of cancer on younger adults.

It must address both immediate barriers to existing programmes and evaluate longer-term innovation in screening technologies.

Implementing systematic approaches, continuing to invest in research, and learning from international best practices is the way forward.

Ultimately, policies and technologies can only go so far. Screening succeeds when people trust the system, understand the benefits and feel supported in taking action.

The essential ingredient is the population’s proactive participation in cancer screening programmes, to really give life to Singapore’s ambition to be a Healthier SG and Blue Zone where our people live long, healthy lives.

- Professor Ravindran Kanesvaran is chairman and senior consultant at the Division of Medical Oncology, National Cancer Centre Singapore. He is also co-director at the Research Institute for Cancer Prevention, Screening and Early Detection (RISE).