Early initiation of palliative care offers significant benefits to patients in their end-of-life journey, improving quality of life and mitigating symptoms. As the first line of contact for patients and their families, GPs play a crucial role in bridging care and improving outcomes – through early referral for interventions, leading discussions on goals of care and providing continuity of care after discharge into the community.

INTRODUCTION

With an ageing population, the number of patients diagnosed and living with cancer will continue to rise.1 Despite our extraordinary advancements in anti-cancer treatments, disease progression and recurrences are common, and cancer remains a leading cause of death in Singapore.1

A variety of palliative care services are necessary to ensure satisfactory quality of life (QoL) nearing end of life. Palliative surgery, a core tenet of good palliative care, plays a crucial role in the care of terminally ill patients and has the potential to mitigate troublesome symptoms and improve QoL.2

Up to 20% of surgeries performed at major cancer centres are palliative in nature, and up to 40% of palliative patients are considered for surgical interventions.3

Debunking misconceptions of palliative surgery

Unfortunately, there are often misconceptions amongst physicians, patients and their caregivers alike that surgical interventions portend high morbidity and mortality rates without conferring significant benefits during end of life.4

This cannot be further from the truth – evidence suggests high symptom resolution rates after palliative surgical interventions in suitable candidates, with fair improvements in patient-reported outcomes.4 At the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS) and Singapore General Hospital (SGH), a significant and sustained improvement in QoL scores has been reported by our palliative surgical patients.

At the Department of Sarcoma, Peritoneal and Rare Tumours (SPRinT), our mission is to deliver quality palliative surgical care through the incubation and implementation of novel healthcare services delivery strategies, interdisciplinary collaboration, the use of innovative technologies and education.

Through this article, we hope to provide insight into our palliative surgical services and generate greater awareness on the benefits of surgical palliative care.

PALLIATION IN SURGERY – RETURNING TO OUR ROOTS

The history of palliative care and surgery

The term ‘palliation’ is derived from the Latin root word pallium, which means to cloak or mask. The origins of palliative care can be traced back to Canadian surgeon Balfour Mount, who is widely known as the ‘father of palliative care’. He kick-started the hospice movement in the early 1970s and introduced a new comprehensive, interdisciplinary, patient-centred model of care that provided symptomatic relief to dying patients, which subsequently gained traction and spread around the world.2

However, the concept of palliative surgery has been around for much longer. Notably, procedures such as the Billroth I gastroduodenostomy, Halsted radical mastectomy and Whipple procedure were all initially conceptualised to provide symptomatic relief in patients with terminal cancer.3

Traditionally, palliative surgery simply referred to non-curative surgery done to relieve symptoms and restore organ function to improve QoL until death, usually with residual or metastatic disease left behind. Often this includes a secondary objective of improving response to adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation, to potentially slow down disease progression and enhance disease-free survival.4

A paradigm shift in advanced cancer care

Over the years, there has been a paradigm shift from a false dichotomy between end-of-life care and treatment of disease5, to recognising that relief of suffering, enhancing QoL and maximising survival are equally important goals and not mutually exclusive in caring for patients with advanced cancer6.

At SPRinT, we recognise that while there should be a focus on providing cure through extensive surgery, we also acknowledge that there is a need to provide good palliative care through surgery, or other interventions, for selected advanced cancer patients.

SPECTRUM OF SURGICAL CARE FOR ADVANCED CANCER

Essentially, surgical interventions for patients at different stages of advanced cancer can be summarised as follows:

Figure 1 Spectrum of surgical care in advanced cancer (click to expand infographic)

THE PALLIATIVE INTERVENTION WORKGROUP MULTIDISCIPLINARY TEAM

The palliative intervention multidisciplinary team (MDT) workgroup at SPRinT was initiated in November 2020 and provides a platform for interdisciplinary clinical, educational and research exchanges.

The team comprises:

- Surgical oncologists

- Medical oncologists

- Radiation oncologists

- Interventional radiologists

- Palliative medicine specialists

- Specialty care nurses

- Psychologists

- Medical social workers

- Gastroenterology and nutrition specialists

- Oncology rehabilitative medicine specialists

- Occupational therapists

- Physiotherapists

Figure 2 Schematic of multidisciplinary care offered to our palliative patients

The workgroup conducts regular meetings to discuss complex issues surrounding the care of palliative cancer patients.

Due to the diversity of our group, a wide range of services are made available to these patients, including:

- Surgical palliative care

- Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) support

- Novel pain management strategies (e.g., IR guided neurolysis)

- Advanced endoscopy

- Radiation therapy

INTEGRATION OF SPECIALTY PALLIATIVE MEDICAL CARE IN SURGICAL ONCOLOGY

Benefits of early initiation of specialist palliative care

Early integration of specialty palliative care services (palliative medicine physicians, specialty care nurses, medical social workers and psychologists) is essential to optimise the outcomes for palliative surgical patients.7-11 Amongst medical oncology patients, early initiation of palliative care services has been shown to improve QoL, symptoms, spiritual well‐being and satisfactions rates.12-14

At SPRinT, all patients with advanced cancer with a prognosis of less than one year will be co-managed with specialist palliative care teams. This model of care provides a support structure for patients at different stages of their illness trajectory, thereby allowing patients time to discuss, accept and cope with their diagnosis and prognosis.15

Typically, during consultations, discussions on symptom management, illness understanding and education, and patient and family coping are usually focused on in the early phases of disease, while treatment decisions and advanced care planning tend to predominate discussions later in the disease course due to an increased focus on higher-quality end-of-life care.16-17

The key role of GPs in palliative care |

|---|

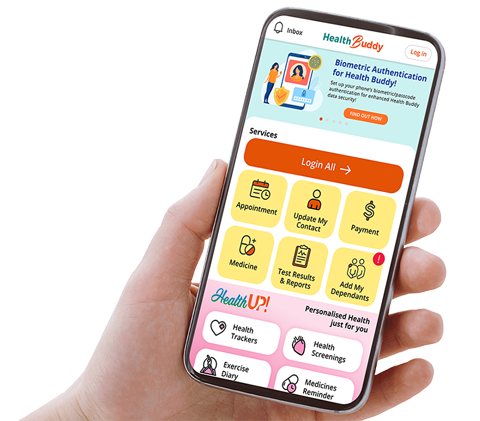

We believe that GPs and family doctors are a key pillar in this model of care, especially given the recent announcement by the Ministry of Health to assign a GP for every household from 2023. Early initiation of palliative care is associated with improvements in one-year survival18, and lower rates of hospitalisation, and intensive care unit (ICU) and emergency department (ED) visits in patients’ last month of life19-20. However, a recent survey conducted by the Singapore Hospice Council in 2020 found that patients were being referred to palliative care services late into their illness journey potentially due to a lack of awareness among patients and community healthcare providers.21 Shared care with GPs As the first line of contact for patients and their families, GPs and family doctors can help identify patients for early referral to our centre for symptom management and palliative surgery, and to facilitate discussions on goals of care. A study by the Lien foundation found that about 77% of respondents preferred to die at home, underscoring the key role that GPs and family doctors can play in bridging care between patients and hospice or hospital-based palliative care providers, and providing continuity of care for the patient and family unit after discharge back into the community.22 Support for GPs to enhance patient care To support our community-based doctors, the Lien foundation and the Singapore Hospice Council conduct yearly courses to equip them with generalist palliative care skills and knowledge to integrate into their practice. With increased awareness, training and engagement of GPs and family doctors in our multidisciplinary approach to palliative care, we hope that patients can benefit from early intervention, better coordination of step-down care and improved outcomes in their end of life. |

NOVEL STRATEGIES FOR PALLIATIVE SYMPTOMS

The development of new and innovative ways to better palliate patients is a priority at SPRinT.

In 2020, we introduced the use of pressurised intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) for patients with advanced peritoneal cancers (Figure 3). This is a novel drug delivery system that enables the aerosolisation of chemotherapeutic agents in the abdominal cavity. It has been shown to result in a more homogenous distribution and greater pentration of anti-cancer treatments, in turn resulting in greater tumour response and symptoms palliation when compared with conventional chemotherapy.

Figure 3 Schematic of PIPAC setup

CASE STUDY |

|---|

Background Mdm A is a 55-year-old lady with existing colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis who presented with cramps in her abdomen, nausea and vomiting. She was subsequently diagnosed with intestinal obstruction (IO) secondary to her peritoneal disease and was placed on the best supportive care due to her poor prognosis by the general surgery team. Patient’s wishes for palliative surgery However, the patient was keen on palliative surgery to relieve her IO in order to avoid tube feeding. This would allow oral food consumption (QoL) and prevent the cost of additional nutritional supplements needed for tube feeding. Furthermore, she had a young teenage son and was keen to be symptom-free and spend as much quality time as possible with her family. Referral to SPRinT She was referred to SPRinT for palliative surgery consideration to optimise her QoL, with the understanding that it would not improve her prognosis and the risks of surgical morbidity and mortality. Mdm A’s case was discussed at our MDT meeting and after careful consideration of patient’s wishes and mitigating factors, such as her health at that time, comorbidities and symptoms, the board collectively offered surgery as an option to the patient. Palliative surgery She subsequently underwent an exploratory laparotomy, partial omentectomy, buthionine sulfoximine (BSO), right hemicolectomy, venting blowhole transverse stoma creation and end ileostomy. At the time of surgery, her prognosis was three to six months. Postoperative care Postoperatively, the patient was started on total parenteral nutrition (TPN) and weaned to an oral diet within ten days following her surgery. She was subsequently discharged after 35 days of hospitalisation, and was able to spend about a symptom-free three months with her family at home before passing away from progression of her disease. She expressed no regrets and was satisfied with her surgical outcomes. |

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES FOR GPs

- Palliative surgery aims to mitigate debilitating symptoms and improve QoL

- In patients presenting with surgical ‘emergencies’, it averts a ‘life-threatening’ crisis and enables patients to be able to ‘live out’ the time they have left.

- Palliation in surgical oncology involves coordination of care between various experts including palliative medicine specialists, specialty care nurses, psychologists, nutrition specialists and allied health professionals. This is essential to ensure quality palliative care.

- Innovation and research in palliative surgical oncology are essential and can optimise the outcomes of patients.

As the first line of contact for patients and their families, GPs and family doctors can play an important role in our multidisciplinary approach to palliative care by helping to identify patients for early referral for intervention, lead discussions on goals of care and facilitate step-down care after discharge from hospice or hospital-based services.

THE SPRinT SERIES: PARTNERING GPs TO CARE FOR ADVANCED AND RARE CANCERS

This is the fourth in a five-part series of articles, ‘The SPRinT Series’ – in which we discuss the work that SPRinT does, the key aspects of SPRinT’s clinical focus and the role of general practitioners (GPs) in providing care.

Due to the rarity of these tumours, it is critical for patients to be promptly referred to a specialist department/centre, such as SPRinT, to provide the best outcomes.

GPs are our first line of defence, and close collaboration between SPRinT and the GP community is essential for the timely diagnosis and referral of patients with rare tumours.

Read the other parts of the series here:

- Part 1: Partnering GPs to Care for Advanced and Rare Cancers

- Part 2: Improving Sarcoma Outcomes with Early Detection

- Part 3: Optimising Management of Peritoneal Surface Malignancies with Timely Referral

For GP referrals to the Department of Sarcoma, Peritoneal and Rare Tumours (SPRinT), please contact NCCS or the Patient Liaison Service (PLS) – GP Network at SGH at: Hotline: 6436 8288 Click here for more information on the department. |

REFERENCES

Singapore Cancer Registry Annual Report 2019. National Registry of Diseases Office HPB; 2022 18 January 2022.

Dunn GP. The surgeon and palliative care: an evolving perspective. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2001;10(1):7-24.

Dunn GP. Restoring palliative care as a surgical tradition. Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons. 2004;89(4):23-9.

Hanna NN, Bellavance E, Keay T. Palliative surgical oncology. Surg Clin North Am. 2011;91(2):343-53, viii.

Gillick MR. Rethinking the central dogma of palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(5):909-13.

Hawley PH. The bow tie model of 21st century palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(1):e2-5.

Rugno FC, Paiva BS, Paiva CE. Early integration of palliative care facilitates the discontinuation of anticancer treatment in women with advanced breast or gynecologic cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;135(2):249-54.

Merchant SJ, Brogly SB, Goldie C, Booth CM, Nanji S, Patel SV, et al. Palliative Care is Associated with Reduced Aggressive End-of-Life Care in Patients with Gastrointestinal Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(6):1478-87.

Nevadunsky NS, Gordon S, Spoozak L, Van Arsdale A, Hou Y, Klobocista M, et al. The role and timing of palliative medicine consultation for women with gynecologic malignancies: association with end of life interventions and direct hospital costs. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132(1):3-7.

Lefkowits C, Teuteberg W, Courtney-Brooks M, Sukumvanich P, Ruskin R, Kelley JL. Improvement in symptom burden within one day after palliative care consultation in a cohort of gynecologic oncology inpatients. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(3):424-8.

Back AL, Park ER, Greer JA, Jackson VA, Jacobsen JC, Gallagher ER, et al. Clinician roles in early integrated palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a qualitative study. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(11):1244-8.

Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, Hannon B, Leighl N, Oza A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1721-30.

Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, Balan S, Brokaw FC, Seville J, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(7):741-9.

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-42.

Moroney MR, Lefkowits C. Evidence for integration of palliative care into surgical oncology practice and education. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120(1):17-22.

Hoerger M, Greer JA, Jackson VA, Park ER, Pirl WF, El-Jawahri A, et al. Defining the Elements of Early Palliative Care That Are Associated With Patient-Reported Outcomes and the Delivery of End-of-Life Care. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(11):1096-102.

Jacobsen J, Jackson V, Dahlin C, Greer J, Perez-Cruz P, Billings JA, et al. Components of early outpatient palliative care consultation in patients with metastatic nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(4):459-64.

Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, Lyons KD, Hull JG, Li Z, et al. Early Versus Delayed Initiation of Concurrent Palliative Oncology Care: Patient Outcomes in the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(13):1438-45.

Scibetta C, Kerr K, McGuire J, Rabow MW. The Costs of Waiting: Implications of the Timing of Palliative Care Consultation among a Cohort of Decedents at a Comprehensive Cancer Center. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(1):69-75.

Blackhall LJ, Read PW, Stukenborg G, Barclay M, Dillon PM, James H, et al. Impact and timing of palliative care referral. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(31_suppl):50-.

Key Survey Findings of Awareness of Hospice & Palliative Care among Healthcare Professionals in Singapore. Council SH; 2020.

Death Attitudes Survey. Foundation L; 2014 8 April 2014.