Radiation therapy, together with surgery and chemotherapy, is one of the three pillars of modern cancer therapy. Radiation therapy involves the use of ionising radiation to kill cancer cells through free radical formation and DNA strand breaks. Since the discovery of X-rays by Wilhem Röntgen in 1896, radiotherapy has evolved from a crude remedy into a precise art, requiring collaboration across a team of doctors, physicists, dosimetrists and radiation therapists to accurately target cancer tissues.

This improved precision has allowed higher doses of radiation to be delivered to tumours, resulting in improved chances of cure and control, whilst sparing more normal tissues and reducing potential toxicities.

Radiation therapy can either be delivered externally (external beam therapy) usually with linear accelerators or internally (brachytherapy) through the use of radioactive elements placed close to the tumour. The most common modalities are photons and electrons, although particle therapy such as proton and ion therapy is becoming more common. Due to the breadth of this topic, this article will focus on the advanced techniques of external beam radiotherapy with photons only.

TREATMENT PLANNING

“If you fail to plan, you are planning to fail!” This quote by Benjamin Franklin is profoundly apt for radiotherapy. Successful treatment planning with radiation therapy requires careful collaboration between all members of the team and due to the complexity of modern techniques, the entire process may take several days to complete.

1. Treatment planning begins with a procedure known as simulation. It involves positioning the patient in a position which is comfortable enough to maintain for at least 15 minutes, and yet suitable for the optimal delivery of radiotherapy.

2. Immobilising the patient through the use of various devices and making tattoos for position reference follows this. If the positioning of the patient is complex, photos may be taken to aid with reproducibility of setup position at the treatment unit.

3. A CT simulation is then performed. For treatment at certain sites such as the lung, 4-dimensional CT imaging may be required. This is so-called because it takes into account motion with time. By acquiring a large number of images over time, the movement of the tumour, e.g. through different phases of respiration, can be viewed. The scanned images are then imported into the treatment planning system software.

4. Defining the region to be irradiated, known as target delineation, ensues. Technology has blessed us with everimproving imaging with higher resolution, allowing greater discernment of tumours. Co-registration of MRI and PET imaging with CT simulation images affords us even more information with which to base target delineation.

5. Combining this with the clinical and pathological information, the clinician then gives additional margins for potential microscopic involvement and uncertainties in position, planning and delivery when deciding the final planning target volume (PTV). This ensures that radiotherapy is delivered as intended to the tumour.

The dosimetrists and physicists use complex computer software modelling, allowing estimations of the radiation dose to the target volume and the normal structures. By varying parameters such as gantry angles and shielding, among others, an individualised plan for the patient can be created.

The total amount of radiation (measured in units called Grays) delivered will be prescribed. This is often divided into smaller doses known as fractions and given over several days or weeks. In certain circumstances the total radiation dose may be given in a single fraction.

All this data is then exported to the treatment machines for delivery of radiation to the patients.

In the early days of radiotherapy, delivery was limited to simple rectangular fields with limited shielding of normal structures. As a result, it was difficult to protect vital structures, resulting in potentially devastating long-term side effects when higher doses were required. By amalgamating our improved understanding of biology and physics, the digital era has ushered new techqniques for us to tip the scales in favour of our patients.

The more advanced external beam therapy techniques include:

- Intensity Modulated Radiotherapy (IMRT),

- Volumetric Modulated Arc Therapy (VMAT),

- Tomotherapy ®,

- Image Guided Radiotherapy (IGRT),

- Stereotactic Radiotherapy (SRT),

- Adaptive Therapy and

- 4-Dimensional Radiotherapy.

1. Intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT)

1. Intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT)

IMRT allows shaping of the dose distribution around the tumour. This is done by delivering the radiation from different angles and the use of multileaf collimators (MLC). MLCs are miniature strips of shields that block radiation in the portal. These work together to create complex radiation fields. These MLCs may remain static (static IMRT) or move (dynamic IMRT) during the delivery of radiation.

IMRT has greatly advanced the treatment of head and neck cancers by allowing dose escalation with fewer severe side effects such as mucositis and xerostomia.

2. Volumetric Modulated Arc Therapy (VMAT)

VMAT technology builds further on IMRT technology. Radiation is delivered while the gantry rotates. This allows adjustment of different variables such as gantry rotation speed, dose rate and MLC position while the beam is moving. Not only can complex dose distributions be achieved, but treatment time is significantly shorter.

This treatment is especially suitable for patients who are unable to remain in the treatment position for prolonged periods of time, but yet require conformal dose distributions, e.g. patients with significant pain.

3. Tomotherapy

In tomotherapy, radiation is delivered much in the same way a CT scanner scans a patient. The treatment couch moves through a doughnut-shaped gantry while the radiation is delivered. Within the gantry, the linear accelerator is able to move around and target the tumour from all angles. The radiation dose is thus delivered in a helix as the patient moves through the gantry.

Together with mini MLC, complex dose distributions can be delivered to large volumes, since a large portion of the patient can be moved through the gantry during delivery. Tomotherapy is often used for many different treatment sites due to the excellent dose distribution that can be achieved.

Together with mini MLC, complex dose distributions can be delivered to large volumes, since a large portion of the patient can be moved through the gantry during delivery. Tomotherapy is often used for many different treatment sites due to the excellent dose distribution that can be achieved.

One group of patients that benefits especially from tomotherapy is those requiring cranio-spinal irradiation (CSI) for tumours such as medulloblastoma or CNS germinoma. In the past, CSI required multiple fields with complicated matching of fields, which was time-consuming for both patient and staff.

Using tomotherapy, the whole cranio-spinal axis can be treated together as one field since the whole area can be moved through the treatment gantry together. Additionally, they benefit from the steep dose gradients that can be achieved.

4. Image Guided Radiotherapy (IGRT)

Image guided radiotherapy refers to the use of frequent imaging during the course of radiation therapy to verify accurate treatment delivery. A scanner is mounted on the treatment machine, allowing images of the treated area to be viewed just before the dose is delivered. This allows verification that the radiation dose is reaching the intended target volume.

By using IGRT, tighter margins can potentially be given when generating the PTV (as mentioned previously under treatment planning). The result is that less radiation is ultimately given to normal tissue around the tumour with potentially fewer side effects.

Patients being treated at sites that may move significantly, e.g. prostate and bladder, benefit from this technique.

5. Stereotactic Radiotherapy (SRT)

Stereotactic radiotherapy is so-called because it enables extremely precise delivery of radiotherapy to ablate tumours. High doses are given in a small number of fractions to treat small volumes, whilst keeping normal tissue dose to a minimum.

This is achieved through tightly-collimated radiation beams with sharp dose fall-off at the edges together with precise patient positioning. Additionally, certain treatment systems allow delivery of radiation through angles on more than one plane (non-coplanar treatment).

Stereotactic radiotherapy is frequently employed in the treatment of early stage non-small cell lung cancers not suitable for surgery. It is particularly useful for solitary or oligometastatic disease, especially in the brain and spine. By focusing the beams onto the tumour with high doses in few fractions, ablation of the tumour is possible.

6. Adaptive Radiotherapy

Adaptive radiotherapy is at the forefront of advanced radiation therapy. During the course of radiation treatment, the anatomy of the patient and tumour may change, for example due to weight loss or tumour shrinkage. Thus, the planned dose distribution of radiation may not match what is being delivered.

Adaptive radiotherapy involves changing, i.e. adapting the radiotherapy plan after treatment has already started and can occur at different time frames. The different time frames are: ‘offline’ between fractions; ‘online’ just prior to delivery; and ‘real time’ during a treatment.

The head and neck is a region that particularly benefits from adaptive radiotherapy. Large neck nodes can shrink significantly during the course of radiotherapy, creating a discordance between planned radiotherapy delivery and what is actually delivered. By adopting adaptive radiotherapy, this can be reduced.

7. 4-Dimensional Radiotherapy

4D radiotherapy involves three-dimensional delivery of radiotherapy, taking into account the 4th dimension of time. As mentioned earlier, tumours may move in the body, for example in the lung during the respiratory cycle.

By monitoring the movement pattern through tracking devices, it is possible to turn the beam on only when the tumour is in the desired portion of the respiratory cycle. This is known as gating. Certain systems employ fiducials or even electromagnetic transponders implanted into the target tissue to allow tracking of the tumour real-time.

4D radiotherapy has a big role in lung cancer treatment. The large motion produced by the diaphragm, especially for lower lobe tumours requires bigger margins and hence bigger target volumes for treatment. This can be abrogated to an extent by the use of 4D radiotherapy.

THE FUTURE – PROTON THERAPY?

Protons are positively-charged subatomic particles that can produce favourable dose distributions. They are produced by machines called cyclotrons and synchrotrons and are then energised to specific velocities, depending on the intended depth of penetration.

As protons travel through the patient, energy is transferred, which results in ionisation. However, most of the energy is transferred right at the end of the path, resulting in a very localised deposition of dose. This opens the door to better dose distribution with more dose to the planned target volume and less to the normal tissues.

One group of patients that benefits greatly from proton therapy is children. The last few decades have seen the overall survival rate in childhood cancers increase from 10% to almost 90%. Since these patients are surviving longer, being afflicted with late side effects is even more detrimental.

CONCLUSION

Radiotherapy continues to evolve since its inception. Technological improvements in imaging and radiation delivery over the last few decades have allowed more precise delivery of radiotherapy in more complex dose distributions.

This has allowed higher doses to be achieved within tumours whilst sparing normal tissues. The increased complexity of treatment requires careful planning and collaboration between all members of the treatment centre.

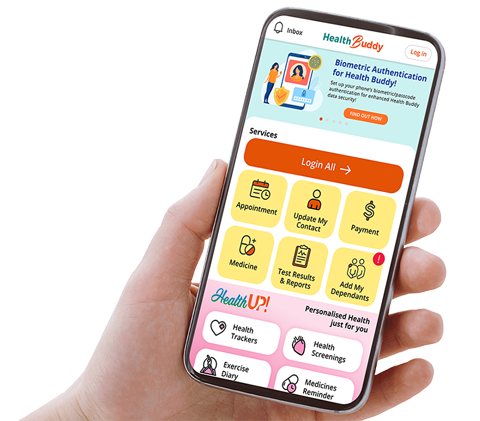

GPs can call for appointments through the GP Appointment Hotline at 6436 8288 for more information.

By: Dr Looi Wen Shen, Registrar, Division of Radiation Oncology, National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS)

Dr Looi Wen Shen is currently a Registrar in the Division of Radiation Oncology of National Cancer Centre Singapore. His main clinical and research interests lie in the field of paediatric radiation oncology.